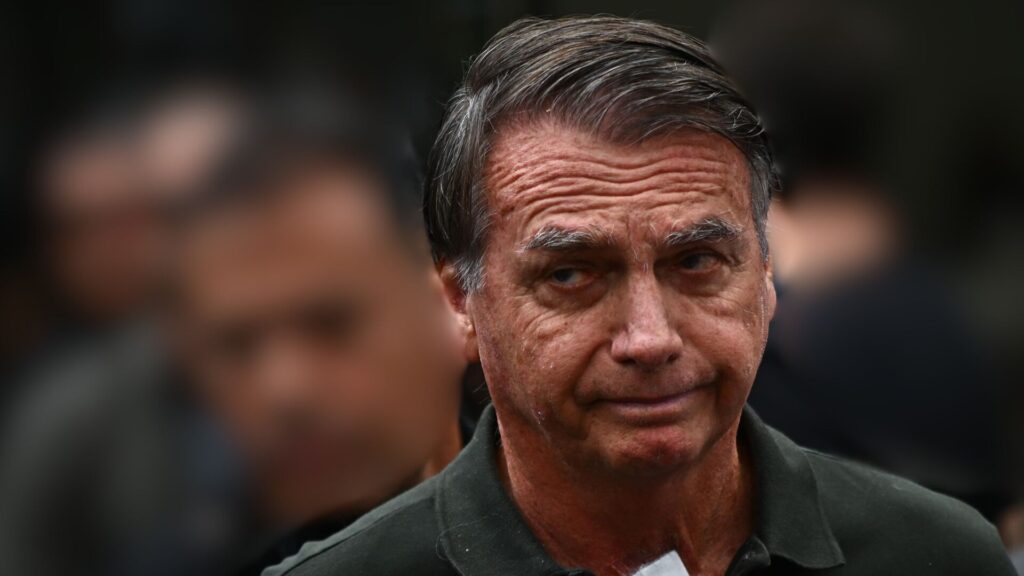

BOLSONARO

Illegal house arrest, illegal pre-trial detention

The entire process to which the ex-president is subjected is riddled with illegalities

The pre-trial detention of former president Jair Bolsonaro, ordered by judge Alexandre de Moraes and confirmed by the First Panel of the Federal Supreme Court (STF), once again launches a fundamental debate: how far should a judge’s power go in a supposedly democratic regime?

One of the principles of Criminal Law is the so-called Principle of Legality. This means that no one can be arrested or punished for doing something that the law does not expressly forbid. If the law doesn’t say it’s forbidden, the judge can’t forbid it. However, the precautionary measures imposed on Bolsonaro – the restrictions that came before his arrest at the Federal Police headquarters – go beyond what the Code of Criminal Procedure (CPP) authorizes.

When Alexandre de Moraes ordered the use of electronic anklets, the judge also banned Bolsonaro from using social media. The CPP has a list of restrictions that a judge can apply, such as nighttime confinement or a ban on contact. Although the law has a loophole for “other obligations”, this should not allow the judge to create restrictions that affect fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression and communication.

When a judge completely prohibits someone from using a modern communication platform, he is not following the law; he is creating a rule of his own. Disobeying an order that is not clearly provided for in legislation is disobeying the will of a judge, not the will of the law. In a state governed by the rule of law, someone could only be imprisoned for going against the law, not for going against the stretched interpretation that a judge decides to give it. What led Bolsonaro to house arrest, which he was serving until last Saturday (22), was having failed to comply with this grotesque measure.

Curiously, the very justification for imposing this restriction was absurd. Another principle of law, the Principle of Personality, which states that a person can only be punished for their own actions, was also violated from the outset, since the electronic anklet was initially imposed on the basis of an accusation against his son, Eduardo Bolsonaro, for the crimes of coercion and obstruction of an investigation.

The justification for Bolsonaro’s pre-trial detention at the Federal Police headquarters was the former president’s “risk of flight”. To support this accusation, Moraes resorted to the same method, reporting that Flávio Bolsonaro, another son of the former president, had called a “vigil” and that a Jair Bolsonaro ally had left the country to avoid arrest. Calling a demonstration is not a crime in Brazil. Even if it were, it was the former president’s son, and not he himself, who called the “vigil”.

Moraes also claims that Bolsonaro’s attempt to break the anklet would increase the “risk of escape”. However, the law does not state that an anklet violation is irrefutable proof of a flight risk. To be legal, the conversion to imprisonment must demonstrate that non-compliance reveals an urgent and current need to guarantee the application of criminal law.

If the order to wear the anklet itself and the other restrictions are illegal because they go beyond the text of the CPP, breaking them cannot be used as suitable evidence to justify imprisonment. It would be like arresting someone for breaking a rule that doesn’t exist in the regulations. The conversion into imprisonment would be based on an original order that was null and void, contaminating the entire process.

The former president was already under house arrest, which makes the order to wear an electronic anklet a humiliating measure. In addition, his residence was surrounded by vehicles from the Federal Police and the Federal District Criminal Police. The security apparatus to prevent escape was already maximum, making the idea that the anklet was the only obstacle to escape ridiculous.

Secondly, the chronology of the facts breaks the direct link between the vigil and the escape attempt. The anklet was broken at dawn, when no “vigil” was taking place. The alleged “escape plan” therefore took place at a time when there was no demonstration or “riot” in the vicinity of the residence, but rather a strong police presence.

Bolsonaro’s pre-trial detention only reinforces the anti-democratic nature of the current Brazilian political regime. The judge does not act according to the law, but with his own head. And in this case, his head is not “his own”, but that of the powerful.

The siege of Jair Bolsonaro is an electoral problem, not a criminal one. Faced with the former president’s refusal to support a candidate more directly linked to big business, the latter, through the STF, is trying to increase the blackmail against Bolsonaro, making it clear that the Court is, in fact, political.